Lithic Futures

Critic: Barry Wark

With: Yagnesh Mehta

Location: Cuzco, Peru.

Type: Gallery Museum

Role: Academic Project

Year: 2024

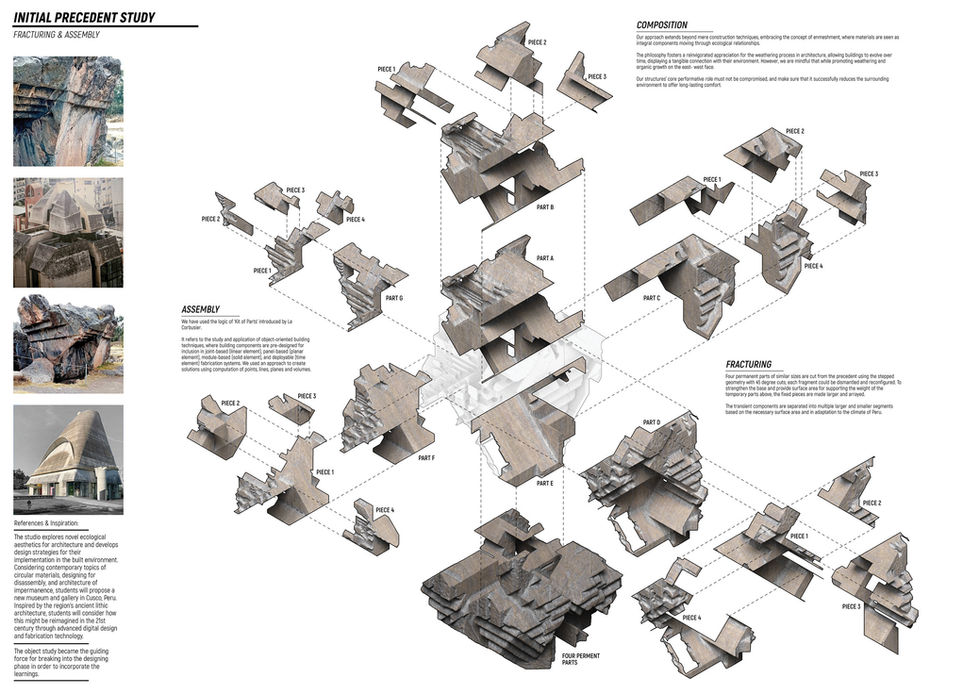

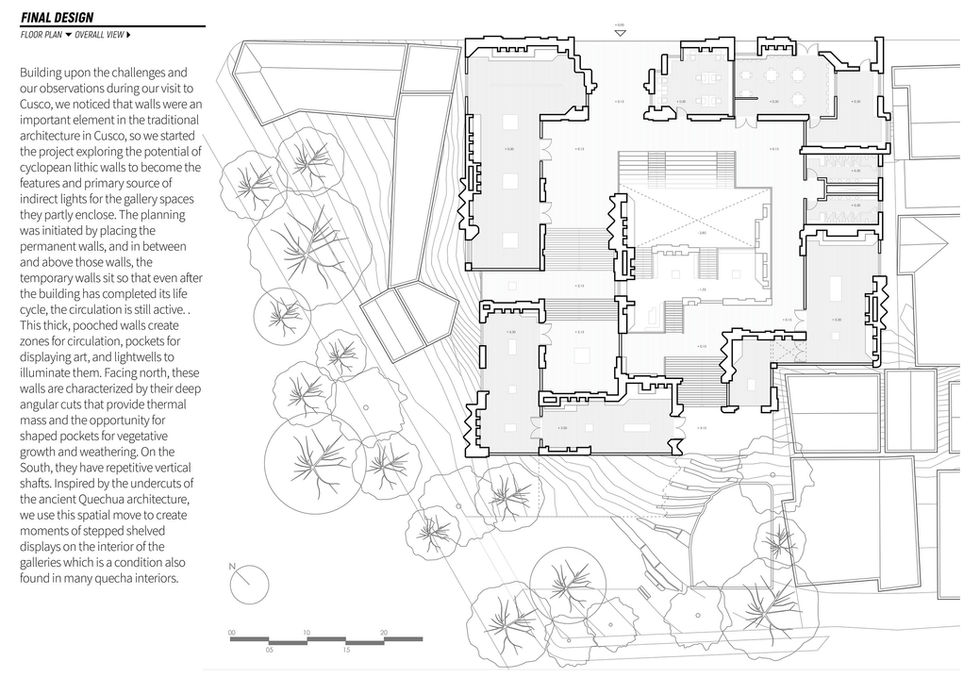

The Project explores novel ecological aesthetics for architecture and develops design strategies for their implementation in the built environment. Considering contemporary topics of circular materials, designing for disassembly, and architecture of impermanence, we proposed a new museum and gallery in Cusco, Peru. Inspired by the region's ancient lithic architecture, considering how this might be reimagined in the 25th century through advanced digital design and fabrication technology. An Architecture of Enmeshment and Impermanence It recognizes that the ideological separation between artifact and nature is no longer appropriate; instead, exploring an architecture of vibrant enmeshment between buildings and their environment. The Project views the idea of enmeshment as both considering the environmental impact of materials as matter moving through ecological relationships and a reinvigoration of the design and appreciation of weathering in architecture. This has created opportunities to design how the qualities of buildings might evolve over time as they display their connection with their environment. That said, promoting weathering, non-determinate plant growth, and the general degradation of our buildings potentially undermines the primary performative function of these structures in mitigating the environment to provide us with comfort. Building upon the challenges and our observations during our visit to Cusco, we noticed that walls were an important element in the traditional architecture in Cusco, so we started the project exploring the potential of cyclopean lithic walls to become the features and primary source of indirect lights for the gallery spaces they partly enclose. The planning was initiated by placing the permanent walls, and in between and above those walls, the temporary walls sit so that even after the building has completed its life cycle, the circulation is still active. . This thick, pooched walls create zones for circulation, pockets for displaying art, and lightwells to illuminate them. Facing north, these walls are characterized by their deep angular cuts that provide thermal mass and the opportunity for shaped pockets for vegetative growth and weathering. On the South, they have repetitive vertical shafts. Inspired by the undercuts of the ancient Quechua architecture, we use this spatial move to create moments of stepped shelved displays on the interior of the galleries which is a condition also found in many quecha interiors. Many digital designs primarily replicate forms and stand out as anomalous structures in their settings, or as Eva Horns frames them. "Nature, in modern aesthetics, has been seen for the most part as something that creates a sense of loss or alienation"1. Eva Horns seems to suggest that modernity has often framed nature in a way that emphasizes disconnection, loss, or estrangement from the natural world, rather than fostering a sense of harmony, belonging, or interconnectedness. Her perception behind this quote likely stems from a critique of anthropocentrism and the dualistic mindset that separates humans from nature. In modernity, rapid industrialization, urbanization, and technological advancements have led to a distancing from natural environments, resulting in a perception of nature as "other" or separate from human civilization. This perception can contribute to a sense of alienation or loss, where individuals may feel disconnected from the intrinsic value and beauty of the natural world, drawing attention in a manner that differs from the subtle allure of biophilic architecture. It's worth noting that the objective of biophilic architecture isn't to evoke feelings of alienation but rather to harmonize with its surroundings, fostering a connection with nature rooted in historical contexts. At its core, emulating nature implies observing the visual features and patterns characteristic of natural objects and integrating them into architectural design. While this approach suggests a preference for natural shape grammars, it’s also about materiality that evokes a sense of grounding and authenticity and also about incorporating elements such as natural light, vegetation, water features, organic materials, and biomimetic design principles, seeking to reconnect people with nature and counteract feelings of alienation or loss. In essence, the concept of novel ecological aesthetics goes beyond mere imitation of form. Our approach emphasizes the building's organic evolution over time, harnessing nature's influence. Strategically designed textures and pockets foster the natural growth of vegetation, while the deliberate cuts and angles in the structure enable moss and water stains to artistically shape the facade. the project reconceives architecture not as a static whole, fixed at the date of its initial construction, but as an assembly of matter constructed and reconstructed where its qualities and configurations are perpetually changing and being regenerated, part by part, thus avoiding trending purely towards obsolescence and ruin. The strategies for this architecture of impermanence speculate on how technology can be used to investigate principles of reconfigurability, reconstruction, and circular materials. It explores the regeneration of structures over time, giving a vision for how we might design for assembly and disassembly, a pertinent topic in contemporary environmental discourse. We envision the structure composed of two distinct materials: the first is the excavated stone from the site's surroundings, referred to as the permanent structure. This material, serving as the building's main skeleton, has no structural life limitation, firmly anchoring the structure to the ground and bearing the load. Without it, the building would collapse. In contrast, the temporary structure consists primarily of printed stone using robotic arms. This approach makes the structure lighter and enhances the potential for reconstruction and reconfiguration after 50-100 years or whenever stakeholders decide to modernize the museum to keep it contemporary. 1. Eva Horn: Challenges for an Aesthetics of the Anthropocene, in: G. Dürbeck/Ph. Hüpkes (eds.): The Anthropocentric Turn, Oxon/New York: Routledge 2020, 159-172.